It was shortly before midnight when I returned to my hotel in the main business district of Panama City. There were several messages for me at the reception desk. One said President George H. Bush was meeting in Washington with his top military advisers and the U.S. was about to invade.

The night that President Bush invaded Panama 30 years ago

It was the largest U.S. military intervention in Latin America, and I was fortunate enough to be on the ground covering it. Besides ending the dictatorship of Gen Manuel Noriega, it was also a life-changing event for me personally.

(Lea este articulo en español)

Over dinner earlier that evening I had postulated that the United States was never going to invade Panama to topple the dictator Gen Manuel Noriega. As a trusted U.S. military source had told me, “Bush’s bark is worse than his bite.”

Little did I know how soon I would be eating my words.

Suddenly, distant explosions began to shake the tall plate glass windows of the hotel lobby.

The rest of that evening is a bit of a blur. I spent most of it in a small room behind reception with Mildred Pottinger, the hotel operator, who kept several lines open for me so I could file regular live radio reports for the BBC in London and national Public Radio in Washington. As we didn’t have cellphones, email, or internet in those days, but my editors kept me supplied with faxes of the latest news from Reuters and the Associated Press.

I made periodic trips to the roof of the 13-floor hotel to survey the aerial assault, watching as AC-130 Spectre gunships strafed Noriega’s downtown headquarters, ‘La Comandancia’, with canon fire and 105 mm howitzers, lighting up the night sky with their glowing red tracers. Before long the Comandancia was engulfed in flames, which also spread to the surrounding poor neighborhood of El Chorillo, with disastrous consequences for the residents.

To my good fortune, the hotel night staff included a number of young Panamanian blacks from the Chorillo neighborhood, a poor slum district where La Comandancia was located. They fed me eyewitness reports, sometimes scribbled on pieces of paper from their friends and relatives describing American tanks moving through the streets and soldiers on loudspeakers warning residents to stay indoors.

The assignment

My invasion assignment has begun a week earlier when I got a call from Newsweek magazine asking if I would go to Panama for Christmas and the New Year in case something happened - all expenses paid.

I was based at the time in Nicaragua and covering the Central American region as a freelancer for British and American media. I was happy to accept the assignment as earlier that year, while covering an aborted presidential election in Panama, I had met a charming young Spanish school teacher.

Meeting Ines Lozano had several advantages for me. Noriega had imposed strict immigration controls and members of the media were not allowed into Panama without first obtaining a special journalist visa. As the daughter of the Spanish ambassador, Ines had a diplomatic passport. She also worked at a U.S. Department of Defense school in Panama as a special education teacher and knew the country well.

So, when I returned to Panama a few months later, just four days before the invasion began, Ines was there to meet me at the airport. I was trying my best to look like a tourist with a tropical shirt and had my reporter’s gear hidden – a tape recorder, microphone and primitive Tandy 200 laptop - stuffed under dirty laundry in my suitcase. Ines was armed with a hotel reservation for a weekend fishing on Contadora Island in the bay of Panama. With her diplomatic passport and a bit of personal charm, she whisked me past with Noriega’s feared G2 intelligence officers at immigration control, with barely a question asked.

It was December 15, and I had arrived just in time to see Noriega declare himself head of state, famously wielding a silver machete at the podium.

After filing my report, Ines and I headed off the next day to Contadora Island, just a 15-minute hop in a small plane across the bay. I still have the photo of a fish – a ‘bonito’ (tuna family) – I caught that day with a long line off the back of the boat.

The next morning at breakfast the waiter brought a telephone to our table. It was an editor at NPR calling to tell me that the previous night an off-duty U.S. Marine, Lt Robert Paz, had been killed at a checkpoint near Noriega’s Comandancia, raising the possibility of a U.S. military response.

Notas Relacionadas

The forgotten U.S. Marine whose death triggered an invasion

Our weekend getaway was over. I just had time to go to the hotel kitchen and pack my fish in ice before we flew back to Panama City on the first available flight.

Two nights later, the invasion began.

The morning after

During the first 48 hours of the invasion I didn’t get a wink’s sleep. On the first morning I walked through chaotic streets to get to the National Assembly, about a mile from my hotel, to watch the swearing in of the new government of President Guillermo Endara, under the protection of U.S. soldiers and armored personal carriers outside. Thanks to Panama’s excellent public phones, I was able to do live radio interviews from the street. All I had to do was press ‘0’ and a friendly Panamanian voice would answer, and I would ask to be put through to the BBC in London, NPR in Washington or CBC in Toronto.

I was astonished to see the U.S. soldiers standing by passively as looters carried off TV sets and furniture, an image which – combined with the burning streets of El Chorillo - would soon cause international outcry over the manner in which the Pentagon had overlooked the U.S. responsibility to preserve law and order in its quest to capture Noriega.

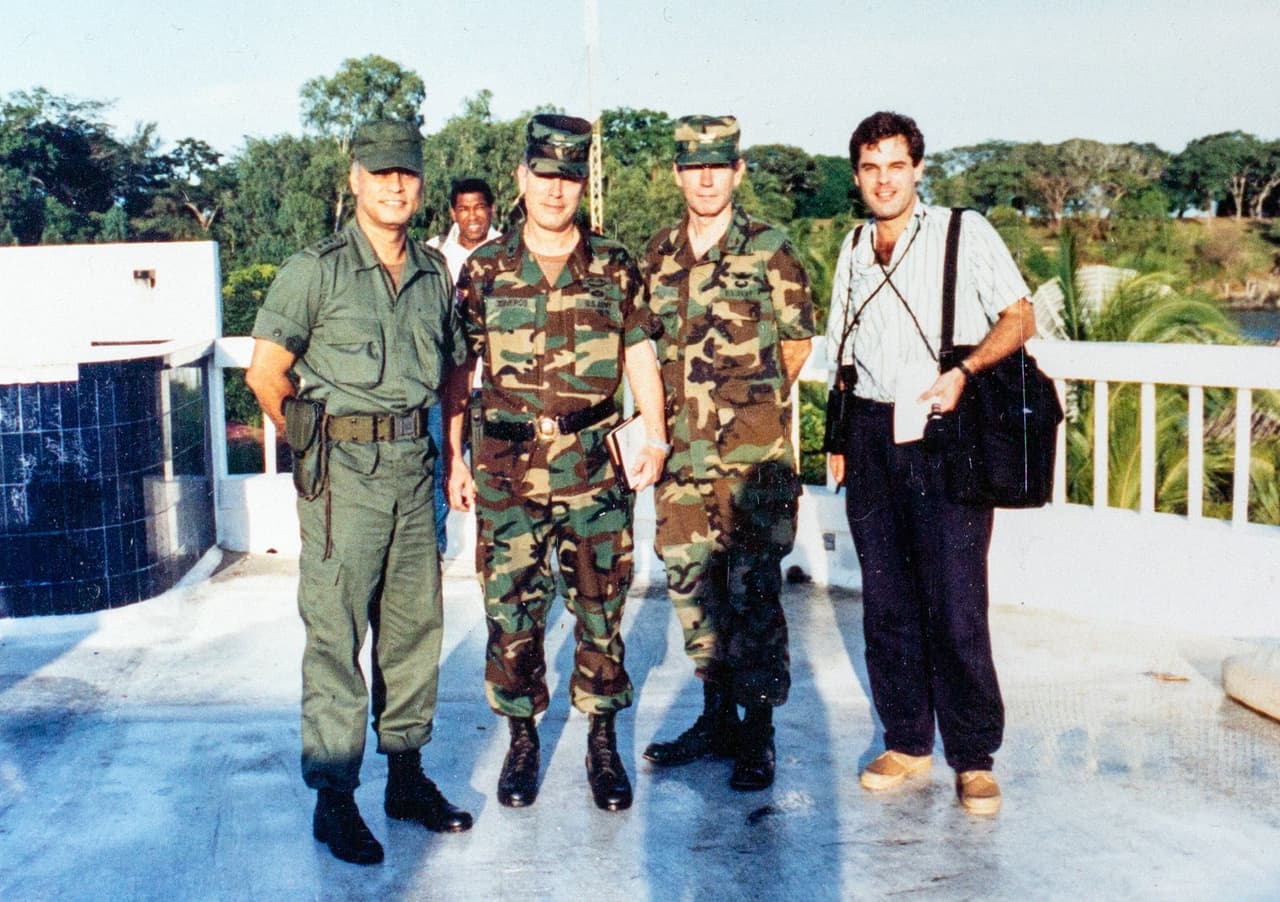

At the time the United States had 12,000 troops stationed in Panama at a series of large military bases along the heavily guarded Panama Canal Zone, under the command of General Maxwell ‘Mad Max’ Thurman, who was widely disliked by his troops who considered him ill-suited for the job since he lacked combat experience and was ignorant about the realities of Panama. Fortunately for Thurman, the head of the U.S. Army contingent in Panama, Gen Marc Cisneros, was his total opposite. A Spanish-speaking South Texan, Cisneros was a Vietnam vet, widely admired for his human touch.

Cisneros had warned the Pentagon – and Thurman - of precisely these consequences and had urged the deployment of Military Police to patrol the streets, but he was ignored. Cisneros, and other officers who knew Panama well, had favored a more limited strike, sensing that Noriega’s ill-equipped defense forces would capitulate without much of a fight. The Pentagon, led, by Gen Colin Powell, had preferred a doctrine of overwhelming force to limit U.S. casualties.

Meanwhile, Ines was trapped in the Spanish embassy with her father and brother. They had all been supposed to fly to Spain for Christmas on Dec 21, but all flights were cancelled for weeks after the international airport was badly damaged during a parachute assault by U.S. Rangers backed by more AC-130 gunships.

But I wasn’t able to see her for several days because the Spanish embassy was surrounded by tanks and razor wire. That was because the invasion suspected that Noriega might try and seek refuge in the Spanish embassy, or the Cuban embassy next door.

The Spanish embassy did take in a few people, mostly journalists, including a team from El Pais, reporter Maruja Torres and photographer Juantxu Rodriguez. They had fled the Marriott hotel after it was taken over by the paramilitary ‘Dignity Battalions’ (Batallones de Dignidad). Several reporters were taken hostage in the basement, including Lindsey Gruson of the New York Times who later described spending a harrowing night with a gun shoved in his mouth. I had been warned by Ines’ father not to stay at the Marriott because he knew the phones were tapped by Noriega, who also had spies there.

I was staying at a less fancy Hotel Ejecutivo, which was also closer to the action downtown. For the first couple of days there was just a handful of people in the hotel. Then journalists started arriving from all over the world.

I was able to speak to Ines on the phone. She told me they were sleeping on the floor in the hallway due to the presence of snipers in the surrounding buildings and they could hear gunfire close by outside. US troops shot up a vehicle right outside the embassy killing several people.

As there were no staff, Ines was helping her father by serving breakfast to the embassy guests. That morning she had breakfast with Juantxu. He left the embassy shortly after to go back and pick up some clothing at the Marriott. Tragically, a firefight erupted right outside the hotel and he was shot in the head and killed. Another French photographer, Patrick Chauvel, was also shot in the stomach in the same incident, but miraculously survived. It turned out to have been friendly fire between US troops.

Before he died Juantxu famously took an important photo inside the Panama City morgue that painted a more dire picture of civilian casualties than the Pentagon briefers were giving.

As the fighting subsided, attention turned to Noriega who was still on the loose. U.S. Special Forces were searching for him high and low. I made an appointment on Christmas Eve to see Joseph Spiteri, the secretary of the Vatican ambassador. The ‘Papal Nuncio’ was the dean of the diplomatic corps and had eyes and ears everywhere. I remember walking there as it was close to my hotel and was surprised to find the gates were open and so I walked up to the door.

After a delay, I was told Spiteri was unavailable. I was given a message with his apologies, adding that I should phone him. Back at my hotel a few minutes later I turned on the U.S. Armed Forces radio to hear Gen Thurman declaring that he had received word that Noriega had taken refuge at the Vatican embassy. No wonder I had been turned away at the door, I thought. I picked up the phone and called Spiteri. When he answered, he confirmed the news and offered me one other vital fact about his boss, the Vatican ambassador, Monsignor Sebastian Laboa.

A Basque from San Sebastian, on Spain’s north coast who worked out lifting weights each morning, Laboa’s previous job at the Vatican was the ‘Devil's Advocate.’ I was unaware that the popular phrase actually originates from the Vatican office where a form of trial is conducted to debate the merits of candidates for sainthood and the recognition of miracles. The Devil’s Advocate is the person who argues against the canonization of a candidate in order to uncover any character flaws or phony evidence of divine intervention.

In other words, Noriega was no match for Laboa, according to Spiteri, who confidently predicted his boss would psychologically disarm the dictator in a matter of a few days.

Outside the embassy, crowds gathered wearing t-shirts that read: ‘Laboa suelta la pina’, depicting a large boa constrictor wrapped around a pineapple, the fruit often used to make fun of Noriega’s pock-marked face, scarred with acne. U.S. troops surrounded the embassy with tanks and loudspeakers blasting rock music, including tunes like “I Fought the Law and Law Won.”

Sure enough, a week later, Noriega meekly emerged and surrendered to the U.S. troops outside.

A few months later, Laboa invited me to dinner with Ines. He’d heard we were dating.

He told us some stories about his days hosting Noriega. Contrary to some reports, the rock music hadn’t bothered him,” he said. He had used ear plugs, and the music was good for pumping iron during his morning workout.

Then he explained why he’d wanted to see us. He’d be leaving for a new posting soon. Before he left Panama he wanted us to know he thought we’d make a good husband and wife and said he hoped we’d get engaged, preferably then and there.

As Noriega had learned, you don’t argue with the Devil’s Advocate. And anyway, he was right, so we did.

We were married a year later, just in time for me to travel to Miami to cover Noriega’s drug trafficking trial.