WASHINGTON. The first thing that you see when you walk into the office of Donald Trump's favorite immigration think tank is a collection of dolls and drawings of the Statue of Liberty decorating the walls: Mickey Mouse and Tweety, as well as a Barbie posing as Lady Liberty raising her torch ... with the Simpsons inside her crown.

Man of the moment: Mark Krikorian, the influential immigration hawk of the Trump era

The leader of Washington's most important "low-immigration" think tank had been waiting decades for plans to secure U.S. borders that include not only undocumented immigrants but also legal immigrants.

In a corner hangs a picture with an especially jarring message. It shows an image of the Statue of Liberty pointing an index finger with the title: "Make America a Better Place. Leave the Country."

Mark Krikorian, director for the Center for Immigration Studies (CIS), clarifies that this picture is a 1968 Peace Corps poster. The federal agency was not intending to intimidate immigrants but to encourage United States citizens to go out and volunteer in the Third World.

The collection is "just a playful reaction to the 'give me the tired and the poor' ideology," explains Krikorian; a snide joke against the symbol of U.S. openness to foreigners.

Notas Relacionadas

Meet the 15 immigration hawks defining Trump's agenda

Krikorian, 56, works in this modest office in one of the buildings on K Street inhabited by Washington lobbyists.

With only 15 employees CIS is tiny compared to other big think tanks, but there's more than meets the eye. With the change of guard in the White House, Krikorian's friends are now in power, and he has gone from being a marginal figure in Washington to an influential political actor.

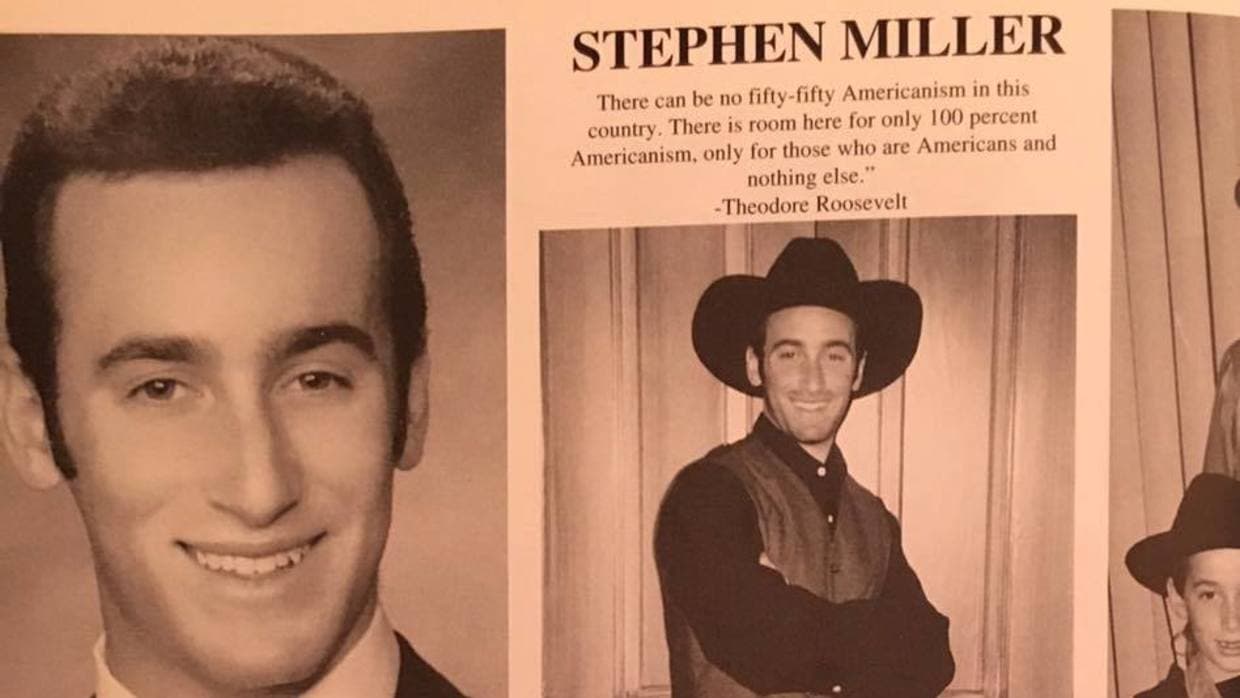

Advisor Stephen Miller, chief strategist Steve Bannon and Attorney General Jeff Sessions are the visible faces of the nationalist 'America first' front in the Trump government. But Krikorian and his CIS researchers are playing a no less important behind-the-scenes role, providing them with studies to promote negative stereotypes about immigrants as part of their closed-border legislative agenda.

This week, Trump and his young adviser Miller brandished CIS studies to justify a bill that would radically cut the number of immigrants in the United States.

The measure, which would mean the biggest reform of the legal migration system in decades, seeks to prioritize those immigrants with higher education and job qualifications, over those who have family ties in the U.S.

For example, Trump said on Wednesday during a White House speech backing the bill that more than half of immigrant households receive some form of subsidy. The Cato Institute and others have said that data is an exaggeration and was calculated without any reasonable statistical methodology.

At a press conference also Wednesday, Miller refered to CIS studies that say immigrants take jobs away from Americans, a claim challenged by other studies. In the same appearance he questioned that the Statue of Liberty is a symbol of immigrants, claiming instead it was an image of "American liberty enlightening the world."

It was all music to the ears of Krikorian. "They cite us and that's how you define success if you are a think tank," he says.

CIS also worked behind the scenes in drafting the immigration bill - known as RAISE (Reforming American Immigration for a Strong Economy Act) - along with Miller and the sponsoring senators, Tom Cotton (R.- Arkansas) and David Perdue (R. - Georgia).

"They ran some of the provisions with us a couple times," says Krikorian who adds that the drafters wanted to basically make sure that they wouldn't complain to the media about it being too soft. "I was just looking for landmines."

For Krikorian, it was a week that marked a milestone in his long career of 22 years as head of CIS that saw the longstanding debate over undocumented immigrants shifting to legal immigration, which he considers the most important question.

"Enforcement is obviously necessary but what the national interest demands in my opinion is that legal numbers come down, not just arresting a lot of people, which is important, but that's an ancillary thing," he says. Krikorian envisages a near future in which the U.S. will look more like the homogeneous society of the 60s, the moment before the beginning of the current immigrant boom, which he's fighting to reverse.

Raised among immigrants

Krikorian has spent his entire career trying to evade accusations of racism and bigotry. He happily agreed to an interview with Univision News and seems delighted to spend 90 minutes explaining his background and the history of the modern movement to restrict immigration.

Unlike other radicals within his movement, Krikorian is used to dealing with immigrants. In fact, he grew up among them. His grandparents arrived in the United States escaping from the genocide in Armenia at the hands of the Ottoman Empire at the beginning of the last century.

As a child, his parents were deeply immersed in the Armenian community, where they found help and compassion in different cities. His father moved from one job to another as chef and manager of restaurants in New Haven (where Krikorian was born), Boston, Cleveland and Chicago.

His parents spoke to him in Armenian, so he did not learn English until he began kindergarten. After studying at Georgetown University and doing postgraduate studies at Tufts University, he spent two years at Yerevan University in Soviet Armenia. Today he is still connected to the community of his ancestors, attending Sunday services at an Armenian church in Washington where he serves as deacon.

Many find it a contradiction that Krikorian developed such negative ideas about immigration. Quite the contrary, he says his familiarity with the immigrant experience has helped craft his ideology. "That's why I don't have a romantic or sentimentalist view about it," he says.

What drew him to fight against immigration policies was his conviction that foreigners must learn English to integrate into American society.

When he came back in 1988 from studying in Armenia, he knocked one day on the door of U.S. English, a group that promotes linguistic assimilation, and was told he better try his luck in the same building where a new group fighting to reverse immigration policies, The Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR), was looking for a newsletter writer.

Shortly after, Krikorian left FAIR to venture into journalism. But the connections he made there served him seven years later to be hired as CIS's executive director.

Krikorian has a glass eye that gives his look the lost air of a philosopher. He laments that his cause is damaged by some more hot-headed "restrictionists" (the name he uses for fellow minded activists) who have a tendency to lose their temper.

"I'm an NPR-style immigration restrictionist," he says jokingly, in reference to the restrained tone of public radio. He advocates that members of his movement focus more on substance than on emotions. He calls it "daring to be dull."

"Compared to other immigration restrictions, he is very accessible, conversational and relaxed," says Alex Nowrasteh, an immigration analyst at the libertarian and pro-immigrant Cato Institute.

Krikorian says he recommends that his people interact more with immigrants in order not to dehumanize them, because "you often find too many people getting carried away by that thing that Mexicans are rapists."

But pro-immigration activists who have dealt with him in radio debates and panels believe that Krikorian is nothing more than the public relations face of a movement based on hatred and division. "He's exactly what he needs to be: media-friendly, reasonable-sounding," says Lisa Navarrete, adviser to the president of UnidosUS, the Latino activist group formerly known as La Raza.

His critics point out that rather than NPR, his style sometimes resembles that of the national-populist website Breitbart, where he is frequently quoted.

For example, nine days after Haiti's devastating earthquake in 2010, Krikorian made a comment that many labeled racist and insensitive: "My guess is that Haiti’s so screwed up because it wasn’t colonized long enough," he said in a column for the conservative publication National Review.

The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) designated CIS for the first time in February as a "hate group" following an investigation which, among other reasons, cited that Krikorian's group shares articles from a white nationalist website, VDARE.

The SPLC blacklist has been criticized by some experts as an excuse to silence groups with a conservative ideology. In an op-ed in the Washington Post, Krikorian protested the label, arguing that the list "conflates groups that really do preach hate, such as the Ku Klux Klan and Nation of Islam, with ones that simply do not share SPLC's political preferences."

Notas Relacionadas

Much of the attacks against CIS are based on what Krikorian claims to be "guilty by association." The CIS was founded in 1985 by John Tanton, who was ostracized years ago as racist. Tanton, a Michigan ophthalmologist who shuns public life because of illness, created a network of groups that make up the modern movement to restrict immigration, including FAIR and US English (the latter cut ties with Tanton over his extreme ideas).

Today, CIS, FAIR and Numbers USA are the most prominent conservative immigration organizations in Washington. While CIS ooperates as a think tank, FAIR is dedicated to lobbying, and Numbers USA seeks to mobilize supporters.

These groups say they are not racist and instead say their views are based on a wider concern that rapid population growth is dangerous because it over-stretches existing federal resources such as food, jobs and infrastructure. Over the years their focus has shifted from "population control" to "immigration control," partly to deflect associations with policies such as sterilization control and eugenics.

Krikorian fights against being labeled as "anti-immigrant", and argues that CIS is "low-immigration, pro-immigrant".

He says that CIS has testified in Congress more than any other immigration group, regardless of ideology: more than 100 times in the last 20 years. Just since January 2016, Krikorian or CIS researchers have testified in Congress ten times.

Among his victories over the years is his role in derailing the 2013 legislative plan to legalize millions of undocumented people, during which he worked closely with then-Senator Sessions and his adviser Miller.

For his rivals on the other side of the debate, Krikorian is not really an immigration expert but rather an advocacy researcher. "Their research is always questionable because they torture the data to make it arrive at the conclusion they desire, which is that immigrants are criminals and a burden on the U.S. and our economy," Democratic Congressman Luis Gutierrez told Univision. "It is the worst kind of deception, but politicians, the conservative media and some Americans eat it up because it always looks somewhat legitimate at first glance."

University of Virginia immigration law professor David Martin says that while he does not share Krikorian's positions, he appreciates the CIS reports because they allow him to present his students with a different viewpoint. "The field is getting so polarized that it's a challenge to get students to think more deeply over the issues."

One of Krikorian's apparent contradictions is that he also employs immigrants. His small team incluces Nayla Rush, a researcher of Lebanese origin who just became a citizen, and Kausha Luna, who emigrated with her parents from Guatemala when she was nine.

Krikorian hired Luna to focus on Latin American media in search of trends under the radar of English-speaking media such as the recent increase in the number of Central Americans seeking asylum in Mexico. "Kausha is our early warning system," says Krikorian.

Although these are good times for his movement, Krikorian does not trust Trump. He rejected an offer to serve as a surrogate during Trump's election campaign. Prior to that offer, Krikorian had described Trump as "a bloviating megalomaniac."

He is especially disappointed that the president has not kept his promise to eliminate DACA. If it was up to him, he would only pardon those who arrived at a very early age, conditional on new enforcement measures being passed.

"The Dream Act covers people who are teenagers, 14, 15 years old. That's ridiculous," he complains. Their cases are different, he says, compared to "people who came as infants and toddlers. They've grown up here, their whole schooling has been here, they don't have an accent."

In any case, Krikorian believes that the current political climate favors him. "The underlying political forces that led to Trump's election are not going away," he says. "The disconnect of our elites from ordinary working people is still there."

Even some leading liberal authors like Peter Beinart or Fareed Zakaria have recently recommended that Democrats shift to the right on immigration. A March editorial by USA Today concedes that Trump is onto something with a merit-based system.

Like other immigration hawks, Krikorian believes that a period of much lower immigration is coming soon in the United States, such as that experienced between the 1920s and the 1970s when the total number of immigrants in the country remained steady at between 10-15 million (between 10 percent and five percent of the total U.S. population).

More than 40 million immigrants live now in the U.S. (13.5 percent of the total population), according to the Migration Policy Institute.

He acknowledges that the bill to limit legal immigration presented this week has very little chance of success because a section of Republican lawmakers is staunchly opposed. At the same time, the sponsors have achieved their goal of triggering debate.

"It is not going to pass this Congress because a big change like that would take several Congresses," he argues.

But, if Krikorian has learned one thing after years as a voice in the desert it's patience.

The bill "is only a first step," he says.