There was a time when everyone heaped praise on the Helicoide. Poet Pablo Neruda called the building “one of the most exquisite creations to emerge from an architect's mind.” Salvador Dali wanted his art displayed in what promised to be the most modern shopping mall of the 1950s.

How an icon of Venezuelan architecture became a jail for political prisoners

The Helicoide was going to be a shopping mall. Today it is a prison, and former inmates describe it as a torture center.

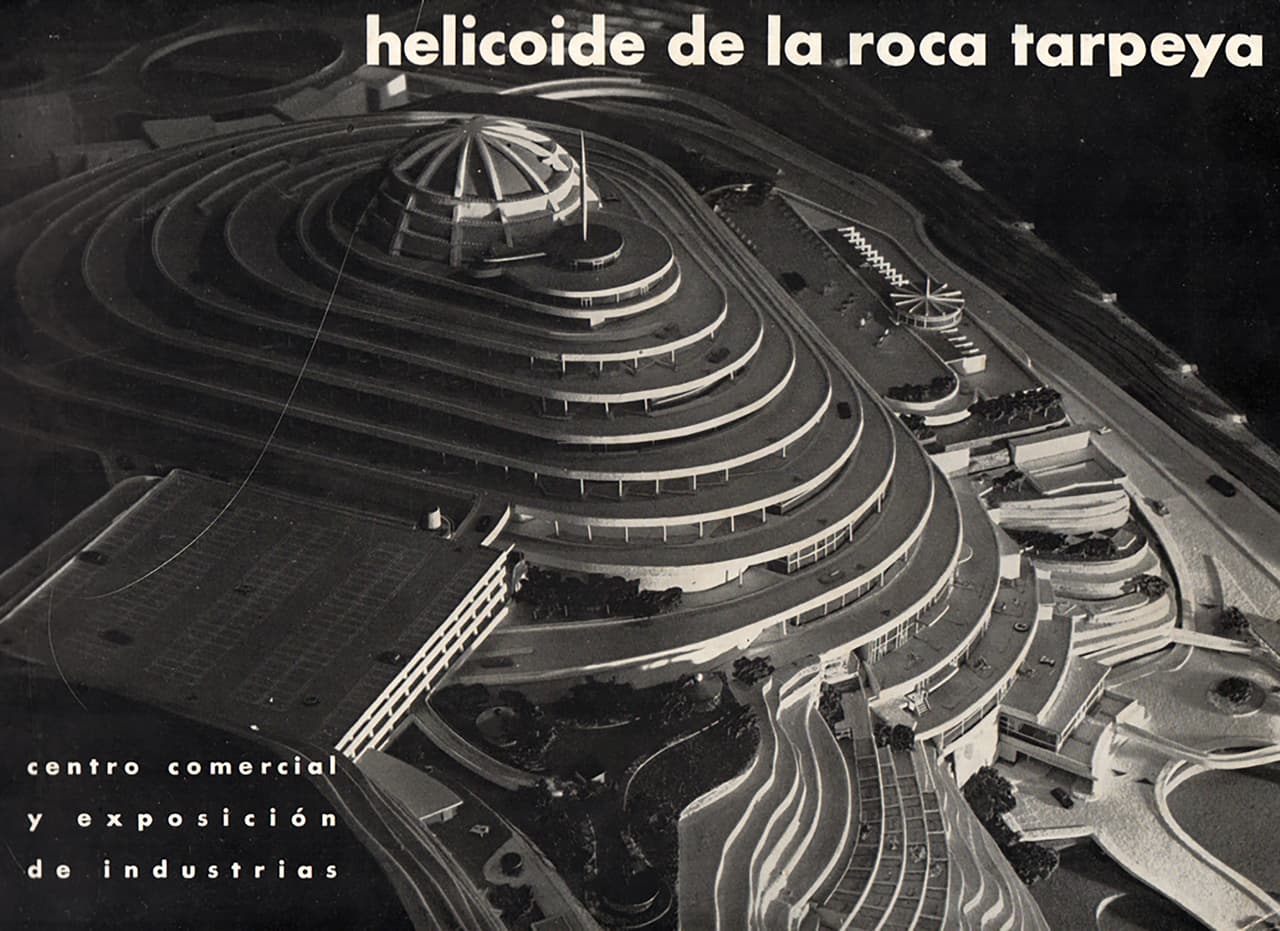

Sixty years later, the building still stands and maintains many of its eye-catching features: a daring structure in the shape of a curved pyramid, with floors that grow smaller in helix-llike fashion as they rise. But today, like much of Venezuela, the building tells a different story.

Sometimes called a “ Tropical Babel,” the building was marked by misfortune and never reached its potential. The one-time symbol of the country's progress wound up converted into a prison and, according to some of its former inmates, a torture center for political prisoners.

Planning for the Helicoide started in 1955, during a period marked by abundant oil money and the dictatorship of Marcos Pérez Jiménez, known for his love of massive construction projects. Everything seemed possible to Venezuelan architects at the time.

“During that wave of optimism … one developer approached (architect) Jorge Romero Gutiérrez and asked for plans for a lot in a place known as Roca Tarpeya where he planned … to build small apartment towers,” architect Dirk Bornhorst wrote in his book The Helicoide. The lot measured 101,000 square meters, about 25 acres.

The company Arquitectura y Urbanismo C. A., where Bornhorst, Gutierrez and Pedro Neuberger worked, created the ambitious design, inspired by the spirals of U.S. architect Frank Lloyd Wright. They adapted it to the steep topography of Roca Tarpeya.

“We are going to build … a super project with Romero Gutierrez. A mountain of shops, with ramps!” Bornhorst wrote in his diary on Jan. 27, 1955.

The original idea was for a shopping mall with 320 stores along the helical structure, plus 1,000 parking place near he shops. The vision would break the mold. Shoppers would be drive, not walk, from store to store.

The Helicoide was to pioneer the use of elevators that moved at an angle through the different levels. It would offer exhibition halls, a gym, pool, bowling alley, nursery and a movie theater with seven screens. It would also include a showroom to sell cars and spare parts, a gasoline station, a repair shop and a car wash. Its own Radio Helicoide would broadcast activities and special offers.

But the project began to fall apart after the Perez Jimenez dictatorship fell in 1958. The political uncertainty that followed reduced sales and the building remained half-finished. The architects eventually lost their investment. In the new democracy, no one wanted anything to do with the project. Although it was started with private capital, its identification with the dictatorship sealed its fate.

The design continued to gather applause abroad for awhile. The Modern Art Museum in New York hosted an exhibit titled Roads that highlighted the integration of the Helicoide's architecture and roadway design, a feature never before seen. It was 1961. But the work was stopped.

From mall to prison

Half a century later, another exhibit in New York is again praising Venezuela's architectural icon. The Center for Architecture is hosting “The Helicoide, from mall to prison,” until July 13. “One of the values of this initiative has been to put this work on display again, as a structure, as architecture, as a cultural phenomenon,” said Celeste Olalquiaga, director of the Project Helicoide.

The exhibit covers the origins of the building, its structure, its failure, its past and present uses and its relationship with Caracas and its people.

“The Helicoide puts in focus what happens with modernity and democracy. Because it was identified with the dictatorship, no one wanted anything to do with it,” said Olalquiaga. “Each successive government then put it to a different use, without any continuity. In the end, they turned it into a living ruin, because it's being used even though it was partially abandoned.”

The building went into a lengthy bankruptcy process and in 1975 became government property, starting the long chain of failed efforts to reactivate or at least make some use of the “white elephant.” From 1979 to 1982, the complex was home to 500 squatter families who lived in shipping containers. Proposals to turn it into a National History and Anthropology Museum never got off the ground. An idea to make it the Environmental Center of Venezuela began to take off in 1993.

Bornhorst wrote that architects Julio Coll and Jorge Castillo climbed to the top of the Roca Tarpeya, meditated in silence and “contacted” the Indians who once lived in the Caracas Valley. That's how they “discovered” that the area had been a tribal cemetery.

“The architects apologized to the energies of the Indian souls for their ignorance. A new conciliatory spiritual environment was created, in which a benevolent, non-commercial goal … allowed three years of uninterrupted work until Venezuela's environmental symbol was finished,” Bornhorst wrote.

But the story of the Environmental Center remained just a story. The new government of President Rafael Caldera abandoned the idea and decided to use the building as the headquarters of the Intelligence and Prevention Services, a police agency known as DISIP. President Hugo Chavez kept the agency there but changed its name to the Bolivarian National Intelligence Service, or SEBIN, and based his new Experimental Security University there.

“A failed and forgotten place like the Helicoide was very convenient for the police,” said Olalquiaga.

“What a contradiction! That a space that wanted to be a symbol of free commerce in the 50s and 60s would later become a jail, a jail for political prisoners,” added Vicente Lecuna, a Central Venezuela University professor and part of the Project Helicoide.

Rosmit Montilla witnessed what happened in the Helicoide for two years, six months and eight days. He was arrested by SEBIN agents on May 2, 2014, and was detained in the complex for alleged links to subversive activities during large anti-government protests that year.

“All that time I was in a cell they called 'Little Hell,'” said Montilla, an alternate member of the legislature from the state of Tachira and member of the opposition Voluntad Popular party. “It was a space five by three meters (15 by 9 feet) that held 22 people. We ate there, slept there, went to the bathroom there. We were tortured with a white light that was blinding.”

Montilla said he also saw how the building was being modified little by little to hold more prisoners. “At first it was just three cells. The rest was administrative offices. Over time, they turned them into cells and torture chambers where they shock prisoners with electricity or hang them to make them talk,” he said.

A report by the non-governmental Venezuela Penal Forum, titled Repression by the Venezuelan Government from January of 2014 to June 2016 documents 145 cases of torture and cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment, the majority by SEBIN and Bolivarian National Guard officers.

“The cases of Gerardo Carrero and Daniel Morales, who were detained in the Helicoide, are clear examples of torture and impunity. After complaints of electrical shocks, beatings or hanging for hours were submitted to the courts, the judges and prosecutors turned a blind eye,” said Alfredo Romero, executive director of Penal Forum.

Olalquiaga said the Helicoide was not designed as a jail, which means its use is essentially a human rights violation and should end.

“That place has a lot of negative connotations. But I don't believe the solution is to veto. It has been stigmatized in recent years, and it has to be freed. Give it another chance. It only makes sense to turn it into a community and sports center, and thereby remedy the mistake of this ambitious project that ignored its immediate context from its beginning,” said Olalquiaga.

That's too easy for Montilla. To this day, he gets angry whenever he sees an image of the building. He is tormented by the thought that other Venezuelans are being tortured there. He misses his jail mates. And he feels pain.

“The Helicoide is a symbol that should not disappear,” he said. “It's a symbol of what Venezuela could have been, and was not. And now it should be kept as a reminder of what happened and what should never happen again.”

Notas Relacionadas