In only two years an associate’s degree could bring you a weekly income of $800, while a college diploma can bring you around $1,200.

Studying while undocumented

Lacking documents is a major barrier into higher education in the United States, but people like José Reza prove that talent and effort make it possible to break past that barrier. Once inside, however, José will have to overcome many other challenges.

Who wouldn’t want to get a professional diploma in record time? Well, pay close attention because what you save in time and money now you could lose in the labor market later.

The basic difference between an associate degree and a bachelor’s degree is that to get the former you would only have to study two years and not four.

Of course, if it’s shorter it’s cheaper: according to data from the College Board from 2010, the average cost of a community college is $2,544, while only one year at a university can be at least $9,000.

José Reza, a Mexican undocumented student at Allen Community College in Iola, Kansas, is getting an associate degree in biology through this community college. But if he faces a labor market with this credential alone he could aspire to be a biologist’s assistant.

That’s why it’s important that a student is well informed and makes sure they can accumulate the necessary credits to transfer to a university that offers a diploma for that profession.

"In this community college I can take 64 credits, which is what a university will also accept,” José told me. “If I take more than 64 credits they won’t accept them, but within those 64 credits I should have the basic subjects: science, math and English.”

Analía Almada is a school counselor at Wakefield High School in Arlington, Virginia. She tells me that an "associate's degree" is an intermediate title that opens up the doors to a four-year university.

The majors that best fit an associate’s degree are in arts, business, communication, digital animation, dental hygiene, culinary arts, auto repair, electronics, among others.

Reza thinks that in such a competitive world, having only an associate’s degree is a limitation and a mistake, but obviously it’s a personal decision. Every student is a world of their own, with their own social and economic drama.

Whatever the type of professional title you choose, it’s important that before you make a decision you explore the work environment in the industry that you are thinking of joining. This could save you disappointments and setbacks in the future.

Many would think that dropping out of college, after fighting for a scholarship and winning it, would be crazy, but before we judge this choice to “self-deport” that José Reza is considering, we’d better walk a mile in his shoes.

On the one hand, this young man from Mexico, who wants to be a biologist, despite his undocumented status, has part of his college and lodging expenses covered at Allen Community College, in Iola, Kansas. He also has in his favor that he was the 'Immigrant Student of the Year for the State of Florida in 2016' and has an outstanding record as an athlete. However, to put it simply, his family has no money to pay for the extra expenses that always come up.

When I refer to his “family”, I am not talking about numerous relations – on the contrary: the only person who can help José is Guillermina, his mother, but she literally lives in constant fear because she lives in Immokalee, Florida, one of the cities where the fear of being deported is destabilizing people’s lives.

"Immigration authorities come to town so often that people are very afraid. They have to keep their doors locked, because they never know who might burst in. It is very difficult for me to know that she is there, alone, with no one to help her", José said the last time we talked.

In fact, Guillermina works 12 hours a day at a food processing plant, and says that the wages she earns are not enough to pay for her son’s college education. So, tired of living in the shadows, she has decided to “self-deport”.

'Self-deportation' means kicking oneself out of the country, when the laws established do not allow people to live and move around freely. Generally, these measures are designed to keep undocumented people from working, having a place to live, being able to get around, and to be afraid to claim health care rights or judicial assistance, among other aspects of normal life.

Our common sense would lead us to wonder: If José’s mother 'deports herself', who can provide economic support for her son?

For José, the answer is obvious: No one. This means he is cornered, between a college dream he cannot pay for, and the alternative of voluntarily returning to Tejupilco to start a life that is not his own.

Something as simple as going to the supermarket could turn out horrible for undocumented college students if anti-

immigrant laws are enforced strictly

Prospects are grim for immigrants living undocumented in the United States. Even if they qualify for a migratory relief program, nothing can be assured. Judging from the way things are going, it seems anyone can be deported.

Two detentions by ICE in the last few days show the scope of President Donald Trump’s new immigration orders. The first questionable arrest was Daniel Ramírez-Medina, 23 years old, in Tacoma, Washington. Although he received permission to remain in the US under the deferred action program known as DACA, he remains impriosoned in the Northwest Detention Center, accused of being a gang member.

Another dramatic case upsetting the immigrant community is the arrest of a transgender woman victim of domestic violence. Immigration agents grabbed her when she came into a county court in El Paso, Texas, to complain about her alleged aggressor.

If we take into account that Trump promised to deport only undocumented immigrants with criminal records, in both cases there is no conclusive proof that they committed any crime at all. Nevertheless, their freedom – on US soil – has ended for the time being.

Now that, according to the Associated Press, the new administration is considering mobilizing the National Guard to help raids to catch people without documents, and Congress already has a Republican proposal to reduce illegal immigration in the US by 50%, there are plenty of reasons for people without papers to be afraid in the fragile bubbles they live in.

Our cameras have been following José Reza’s footsteps for eight months, who – like many other Dreamers – is hoping to get his professional degree. Thanks to his excellent grades, he got a scholarship to the Allen Community College in Iola, Kansas. But now, just the possibility that police departments might share information with immigration agencies keeps him on his toes, enclosed in his bubble.

Since he didn’t qualify for any migratory relief, because he came to the country after 2012, José has no driver’s license, Social Security number, much less a work permit. And in the town where he lives, anyone who can’t drive is technically isolated.

"Ever since Donald Trump was elected President, I've been watching the news very closely... He doesn’t like immigrants and he’s doing everything he can to make our lives harder", says José, as he welcomes us to his dorm room at college.

If a student is caught driving without a driver’s license, he runs the risk of being arrested and then deported, if police enforce Trump’s orders strictly.

So, you ask yourself, how can a student without papers go to the public library without risking being arrested?

How can he get to the supermarket to shop for what he needs? How can he trust a court to protect him from some situation that affects him, when they may just handcuff him right there?

The answer is cruel and tragic, but it is his reality: for the time being, living in a bubble is the best option.

The last thing I expected to find in Iola, Kansas, was a group of students – mostly Caucasian – listening to “ranchero”

music in the game room of their university, the Allen Community College (ACC). This would be like finding people listening to country and western music in the halls of the Autonomous University in Mexico City. Of course, anything is possible, but when you see it with your own eyes you have to document it because it is the most convincing proof that something is changing in this town.

So you can understand a bit about why I was so surprised, Iola is a town in southeastern Kansas with a population of nearly 6,000. Here it is not so common to bump into Latin Americans on the street, the way one does in New York, Miami or Los Angeles.

According to the 2010 census, only 3.1% of the town’s inhabitants are Hispanic. The few restaurants that sell tacos are managed by non-Hispanics. Most people are fair-skinned, and to find people speaking Spanish you might go look around the Community College.

Tracy Lee, an English professor, tells us with a grin, “during the last few years, we have noticed an increase in Latino students at the College, and we are all having fun”.

At the College’s game room, we found young people born in Japlan, Missouri; Houston, Texas; Garden City, Kansas…, almost all blonde and blue-eyed. However, we also found young people with copper skin, and ranging from black to cinnamon-color, who have come from Cuba, Mexico and Central America, with different life stories.

Cuban Alian Barrera, for example, got a scholarship to play on the College’s soccer team. Mexican José Viera explains that his mother is working two jobs to pay for his studies, since the scholarship he got doesn’t cover one hundred percent of his expenses.

José Reza’s case is unique. Univisión News has been documenting his university adventure for seven months, since he graduated from high school in Emmokalee, Florida, up to his arrival in Iola to face the challenge of becoming a biologist, even though he does not have all his papers.

When we caught up with him in the dining hall, he told us that the government grant he receives pays for his studies and is enough to cover his food costs as well. “Every day we get three meals, all paid for; I don’t have to worry about that”, said the 19-year old.

The transition to college life has not been easy for these young people. Lee says it is hard for them to balance their lives, because for most of them it is their first time away from home. And now they face academic responsibilities and economic concerns.

José is a member of the College’s cross-country team. He spends several hours a day training. Belonging to the College’s elite sports team is no small matter. Aside from the intellectual pressure, they have to show what they can do on the track.

The American students say they are enjoying this diversity. Aside from the “ranchero” music that these foreigners brought with them, they are happy with their sports teams’ performance, and many of them are on these teams.

The cross-country team, for example, has won first place in the annual competition among all the universities in eastern Kansas. Unfortunately, José could not compete, because of an injury. Where he is competing hard is in his studies. At the end of the day, succeeding academically is his real goal.

Guillermina Maya never imagined that she would open the door and be surprised by her son, coming home after

finishing his first semester at college. For the first time in six years, she will receive the new year in the company of José Reza, her 19-year-old son who, in spite of the migratory system, has managed to get into higher education in the United States.

For five months now, Univisión News has been documenting the life of this young Mexican who, thanks to his talent and his sports skills, has won a scholarship to Allen Community College, in Iola, Kansas.

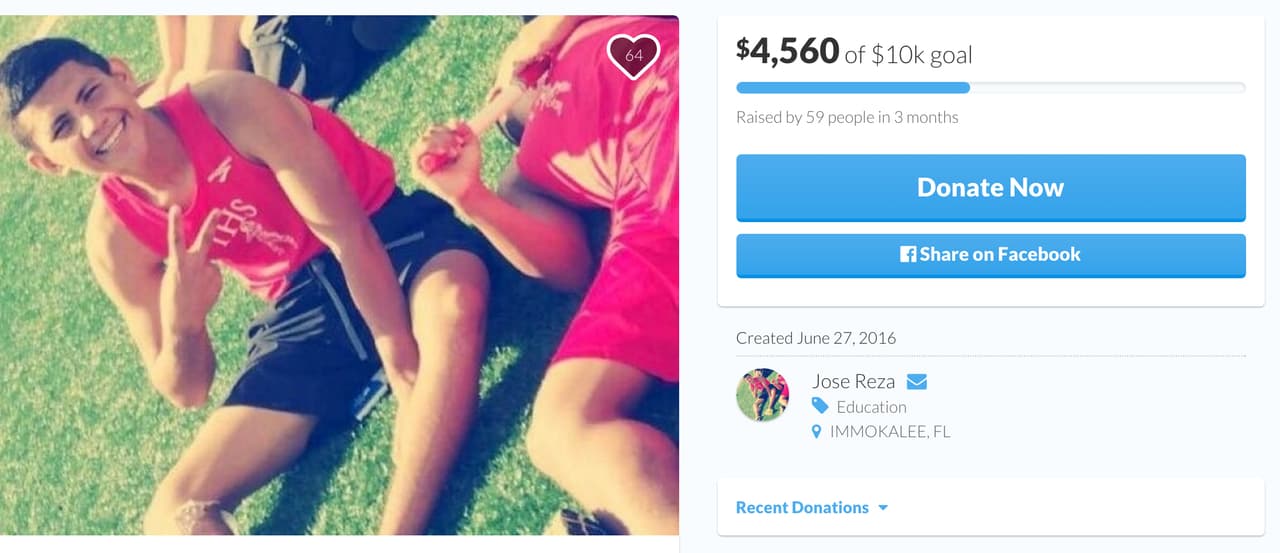

We met him in August, when he received us for the first time in his humble home in Emmokalee, Florida. At that time, he was collecting donations, door-to-door, to finance his studies. Then he opened an account with the Gofundme Website, where he has managed to collect nearly 10,000 dollars.

Our cameras have captured him saying goodbye to his Mother, and José’s first kiss with his girlfriend; we were also there when the cross-country team from the college he represents won first place in the regional championship. José was unable to compete in that contest, because one of his ankles was injured, but he cheered on his other team members.

However, not everything has been rosy during these months at college. The fears associated with his migratory status, which had been lessening, came back strong when Donald Trump won the United States presidency. The new President has promised to put an end to DACA, the deferred action that protects nearly 800,000 young people who have entered the country without papers as children, while deporting millions of people without documents.

José did not qualify for migratory relief, but the fact that he had managed to get a scholarship to an institution of higher learning gave him hope. Now he fears that a presidential order may put an end to everything he has achieved in these months.

Nationwide, students are organizing and, along with their professors, are asking for college campuses to become sanctuaries for people without documents. However, the new administration has threatened to cut back federal funding from any cities supporting this form of protection.

With all of this, 2016 has not been José’s happiest Christmas.

The evening of November 8 th in Iola, Kansas, was a very cold night, with the moon brightly lighting up the pathway to one of the dormitories at Allen Community College (ACC). As I walked that direction, I could see that some college kids were inviting their friends in Spanish to come get together in the building’s lobby, to find out what was going on: Trump was winning by a landslide in almost all the forecasts on television. With the magnate about to win, these young people’s laughter began to turn into expressions of concern.

“I’m especially nervous about my parents. I was born here, but they come from Mexico. I’m worried about what might happen if Trump wins", said Eduardo Herrera, a student who says he is afraid his parents might be among the group of 11 million undocumented immigrants who the President-elect has sworn to deport as soon as he becomes Commander in Chief.

“I would like Hillary to win, because Trump would send many of my relatives away from here”, said Kimberly Rodríguez, a student of Nursing who was unreservedly shouting for the candidate of her preference.

Although the Democratic Party has not been able to materialize any concrete migratory reform over the last eight years, these students’ preference for Hillary Clinton is understandable because she is the only candidate with a pro-immigrant platform. The other option means, for them, a leap into the unknown.

To understand the fear that this college community feels about Donald Trump’s victory, we have to put ourselves in their shoes for a moment.

José Reza, for example, enjoys the privilege of living in a college dormitory facility, because he got a scholarship for being a brilliant student. He is also one of ACC’s top elite athletes. His dilemma is that he is undocumented.

The scholarship covers part of his tuition and the rest is covered by donations that he receives by Internet or directly from generous individuals who support his cause. His mother, who lives in Emmokalee, Florida, could be deported if Trump keeps his campaign promises.

Every new president has to make good on his offers, if he wants to be reelected. In Trump’s case, building a wall on the border and deporting undocumented immigrants are promises that his voters want to see him turn into actions. So, for many analysts, one of the first orders that the real-estate magnate will issue from the Oval Office will be to stop and cancel any migration relief that his predecessor has begun. This would leave dreamers like José without the possibility of continuing their studies – he wants to be a biologist.

“The truth is that I never expected this to turn out this way, but there is nothing I can do about it. Just pray and wait for God’s will to be done", was the first thing that José could say when he heard the news on the television screen, that the most-feared candidate had made it where many never imagined he would get to.

With every mile that José Reza and his two best friends drive the Ford Explorer they bought for this adventure, they get further from their teenage years in Florida, to become young adults at college in Kansas.

The car is full of backpacks, books and – above all – dreams. Each of these young men has had to overcome serious obstacles to reach this new stage in their lives.

“So, I come. Lord I come!”, goes the chorus of the song 'Running in Circles' that the boys are singing at the top of their lungs as they roll down the highway. “It’s a Christian song, because nothing is possible without Him (God)”, says José while Alejandro Ruiz keeps his eyes on the horizon and his hands on the steering wheel, and their Haitian friend, Adonet Thermidor, hunches down in the back seat for a nap.

After 26 hours on the road, Iola welcomes them. This small town in southeastern Kansas, has only 3% Hispanic population.

During their high-school years, it was common for José to run into Latinos in Emmokalee, Florida, and particularly at school: “...Spanish was one of the foreign languages you heard the most, and I was never discriminated against because of my Latino origin”.

But José is aware that college life may hold surprises for him, especially in a town where it is unusual for anyone to speak Spanish.

Allen Community College’s entrance proclaims their commitment to “a policy of non-discrimination for race, skin color, sex, nationality, religion or age”.

However, these young men already know that their transition from high school to college, in a totally different environment from their own, will pose a challenge.

“This is predominantly a community of white people, but in the last ten years it has started becoming more diverse”, says Nicole Peters, the school counselor who will have to supervise the change process in these dreamers’ lives.

When José, Alejandro and Adonet come in the door, they can’t believe that they are standing in the room that will be theirs until they graduate as professionals.

I can see the excitement in their eyes. As they bustle around, trying to organize all their belongings in the compact bedroom, you can see how adrenalin is coursing through their veins.

Especially when they hear the dormitory manager’s warning: “Here, you are the only ones responsible for your actions”.

“We are very happy, the rooms are large, and what we came for is to study and work hard”, mumbles José as he removes his knickknacks out of a cardboard box, which he brought from home to personalize his dresser.

“I’m just ready to sleep!” Alejandro blurts out, diving into the narrow bed that will frame his cares and his hopes.

Alejandro is lucky because his parents, who are from Mexico, are paying his college expenses, so he won’t have to worry about money: “Living here costs 2,500 dollars a semester, and that covers electricity and water. All you have to worry about is your personal things”.

However, José is not that lucky. When we filmed this story, his mother was out of work. His scholarship, and donations he gets by Internet are his only support just now.

“I have the GoFundme page and other teachers donating money for me, clothing and things like that... so everything I have here in my pocket is someone’s gift. In fact, I’d better pay here in a few minutes, before someone tells me ‘you can’t be here without paying!’”, says José.

Peters explains that, although a student without all his papers cannot qualify for federal student aid, there are other alternatives: "He still qualifies for our low-cost tuition as a student, and also for a participation scholarship that covers his tuition and books”.

José is proof that an outstanding student who is also a sports star, can achieve his coveted higher education despite his migratory status. Although he has to overcome many challenges to make this work.

Getting in is only the first step. What comes now for José and his friends is an even greater challenge: adapting to university life. A life where they will have to demonstrate emotional stability and intellectual talent. We will be here to document it all.

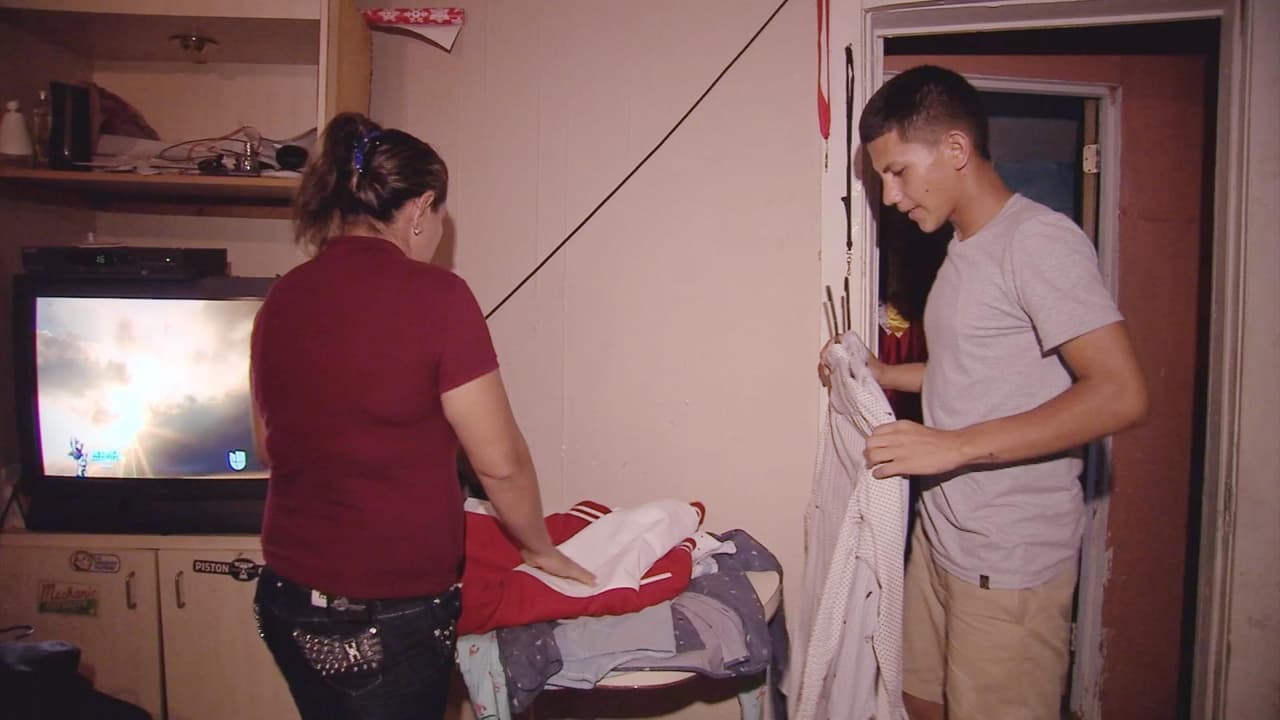

“Give your children the chance to live their life, not yours,” goes the popular saying. And even though Guillermina Maya did not want to, the time has come for her kid, José Reza, to take flight.

“May God and the Blessed Virgin take care of you, I know you will be OK,” this Mexican mother manages to say to her 19-year old son while they hug tightly before our cameras.

It is a hug that closes a stage in Jose’s life. From this moment on, he stops being mama’s spoiled child, to become an independent college student, responsible for his own actions.

The story of how this young Mexican immigrant was able to enter into the higher education system is not too conventional. Jose is undocumented and he did not qualify for any U.S. migratory help.

But thanks to his excellent grades –his GPA score is 4.6–, he obtained a scholarship that will partially cover his expenses at the Allen Community College, in Iola, Kansas.

In order to finance his trip from Florida to Kansas, and pay for food, lodging and other expenses that tend to appear out of nowhere, Jose took a rather peculiar decision: he wrote a letter telling the story of his young life.

“I narrate my odyssey when I arrived from Mexico with my mother, and how she almost looses me in the middle of the desert when we were crossing the border, and I end by saying that I do not want to contemplate the fact that my condition as an undocumented person will stop me from learning,” he tells us.

Days before his trip he goes around stores and businesses in his neighborhood, hoping for his community to become sensitive to his needs and donate some money. One of the donors is ‘Mi ranchito’ restaurant, owned by Juana María Trejo.

“I hope he can get the help he needs, because he has a dream. What I and all mothers wish is that our children make their dreams come true,” she says.

Internet is also an important tool for this dreamer who is looking to finance his new college life. In the site gofundme he created a web page that has already collected 4,560 dollars in a few months.

Tammy Ortiz, one of the donors, said: “When I read your biography, I almost cried. I was planning a garage sale but I was never able to do it because it was so hot. Now, at 7/17/16 I sold about 30 dollars to finance Jose Reza’s education.”

José is very thankful. Even though this campaign will not solve his financial problem, it has allowed him to keep his head up.

“You know that time flies. Two years are nothing, but they will be a lot for me because they will only change my life but yours as well,” he tells his mother as she keeps the tight embrace.

The time has come to say good-bye. Jose and his two best friends wait for him outside his home and are ready to start the 1,400-miles journey from Florida to Kansas.

They will ride on a used car bought for that purpose. On these four wheels they will start writing a new chapter in their life, one that they will never forget.

In Immokalee, Florida, Guillermina and her son José, immigrants from Mexico, live in a humble dwelling, where higher education and a successful career for José once seemed out of the question.

When they arrived to the United States four years ago, neither spoke a word of English. Guillermina, a single mother, was the victim of domestic violence.

José dreamed of going to college, but with no money in her pocket, credit history or legal documentation to be in the United States, Guillermina doubted that her son would be able to achieve his dream to be a biology teacher.

Against the odds, José excelled in high school. A brilliant student and an excellent athlete, José graduated from Immokalee High School with a 4.6 GPA. He won dozens of medals and awards as a member of the cross country team.

After he crossed the border, José found a dictionary and studied English during his breaks from picking fruit. Today he is bilingual.

Without papers, going to college once felt like an insurmountable obstacle for José. But thanks to his academic accomplishments, José earned a partial scholarship to Allen Community College, a school in southeastern Kansas.

Through the guidance of several counselors, he was also able to obtain a foreign student permit that will allow him to remain in the country legally, provided he maintains his good academic record.

But tuition is $7,398 per year and the scholarship covers only 60% of that. That means José still needs $3,000 more, not including living expenses.

How will he raise the money? It’s still unclear, but José refuses to buckle under pressure. He’s adamant about fulfilling his dream to become a biology teacher. He recently set up a website, and Univision News and the Gates Foundation will follow his efforts to raise the money.

Next time we see him, José won’t be in Immokalee, Florida. After his mother bids him farewell, he’ll be pursuing his dreams in a small town in Kansas.

****