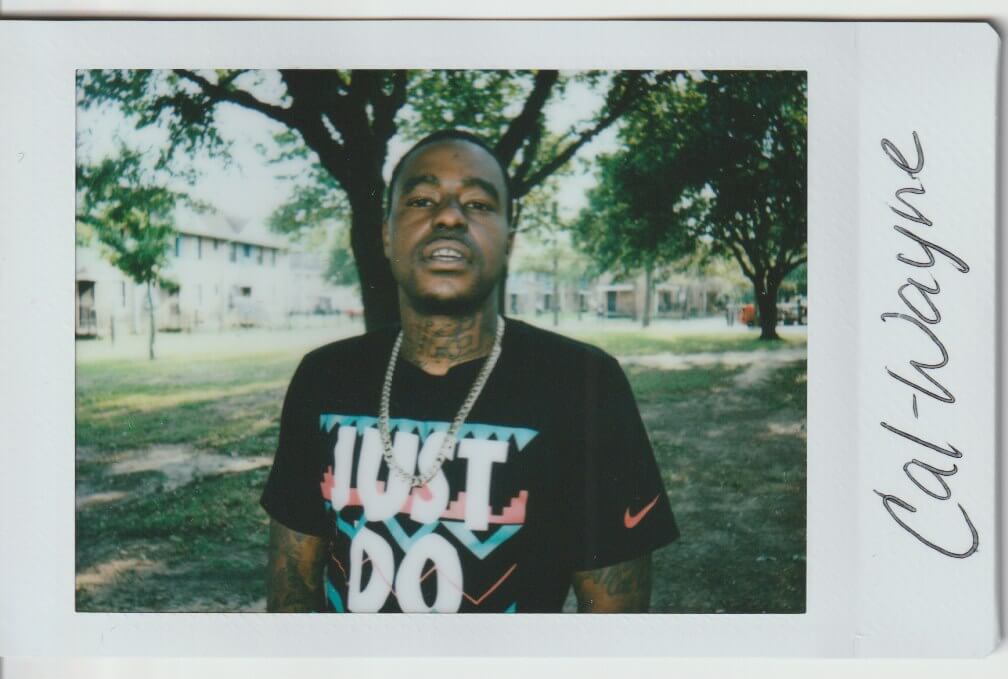

George Floyd: a community leader

May 25, 2021

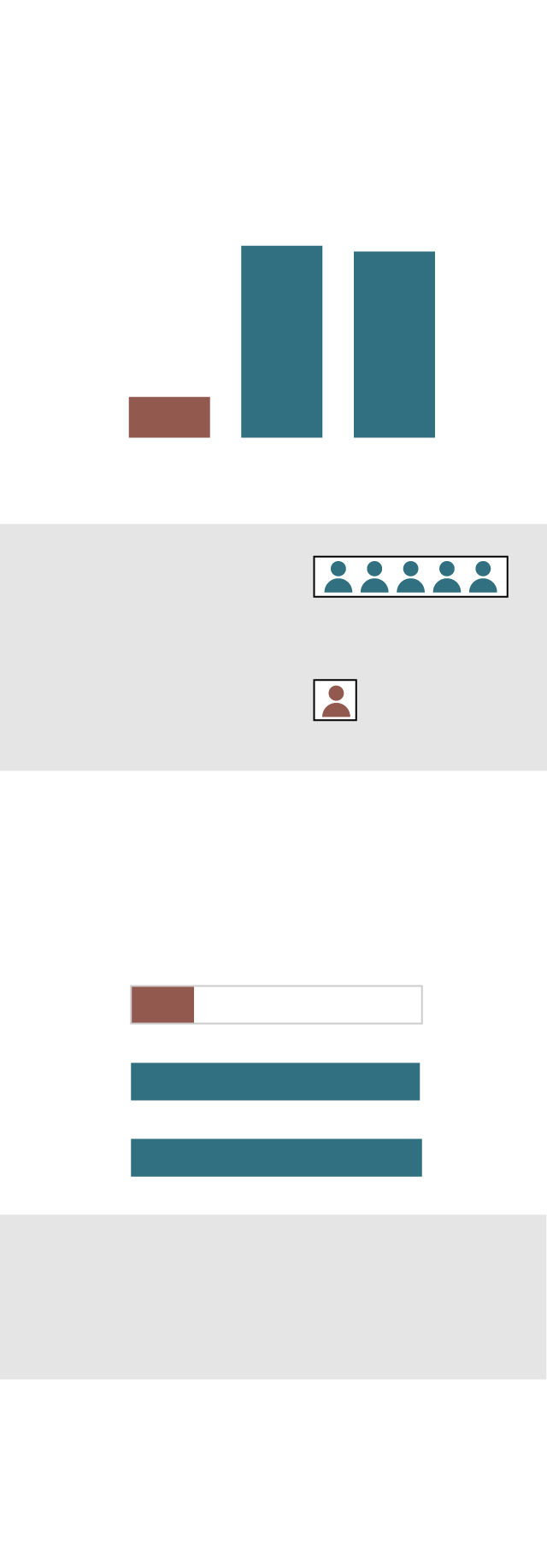

The inequality of Cuney Homes

The proportion of residents with bachelor’s

or other graduate degrees is much lower in Cuney Homes than in Houston or Harris County.

7%

33%

32%

Cuney Homes

Area

Houston

Harris

County

For approximately every

residents (25 years or older) with

a college degree in Houston ...

...there is

in Cuney

Homes.

The annual per capita income among residents in Cuney Homes public housing complex is nearly one-fifth of that in Houston or Harris County.

Cuney Homes Area

$7,081

Houston

$32,521

Harris County

$32,765

The vast majority of families in Cuney Homes have annual incomes below $50,0000. The median household income is around $11,600.

Source: Census Reporter. American Community Survey (2015-2019). Data for the Cuney Homes area corresponds to Block 1, Harris, TX. The margin of error for the population with the highest education in the area is +/- 6.7% and for the per capita income ± $ 1,297.

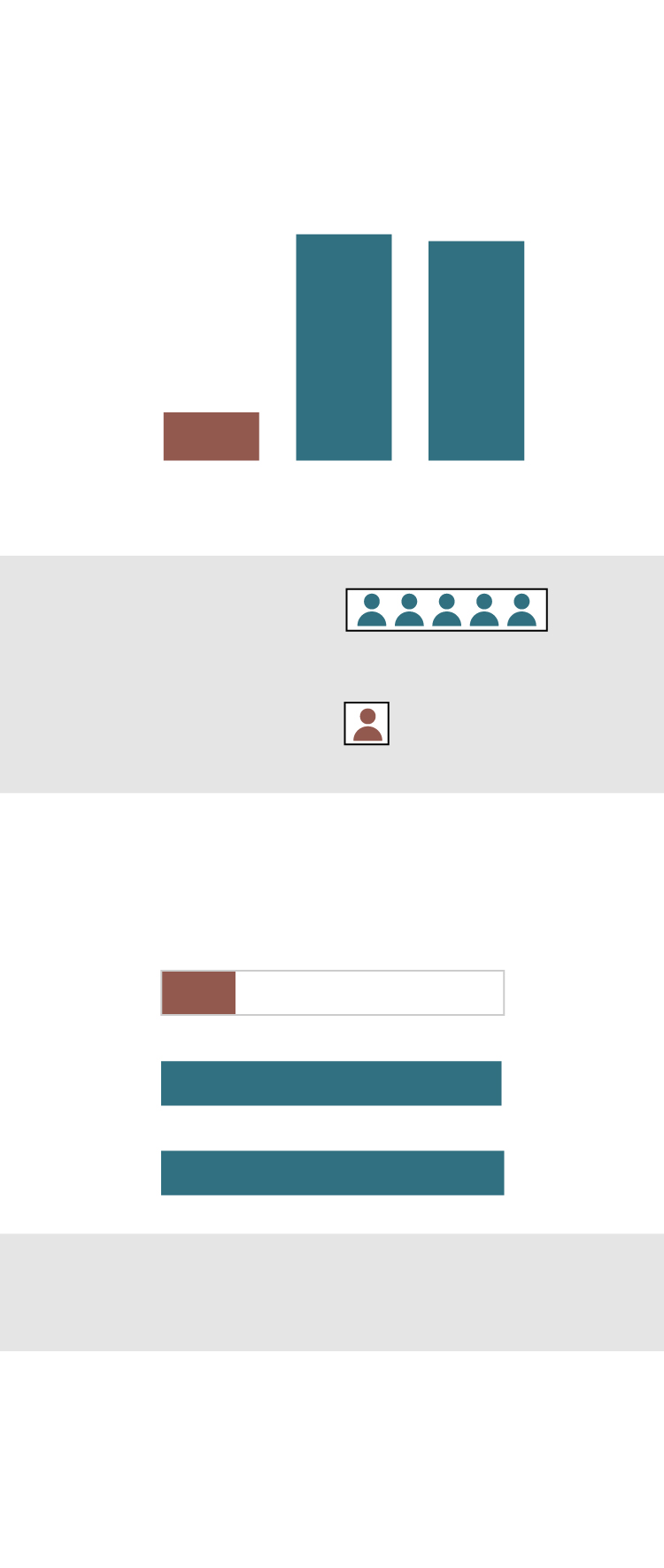

The inequality of Cuney Homes

The proportion of residents with bachelor’s or other graduate degrees is much lower in Cuney Homes than in Houston or Harris County.

7%

33%

32%

Cuney Homes

Area

Houston

Harris

County

For approximately every

residents (25 years or older) with a college degree in Houston...

...there is

in Cuney Homes.

The annual per capita income among residents in Cuney Homes public housing complex is nearly one-fifth of that in Houston or Harris County.

Cuney Homes Area

$7,081

Houston

$32,521

Harris County

$32,765

The vast majority of families in Cuney Homes have annual incomes below $50,0000. The median household income is around $11,600.

Source: Census Reporter. American Community Survey (2015-2019).

Data for the Cuney Homes area corresponds to Block 1, Harris, TX.

The margin of error for the population with the highest education in

the area is +/- 6.7% and for the per capita income ± $ 1,297.

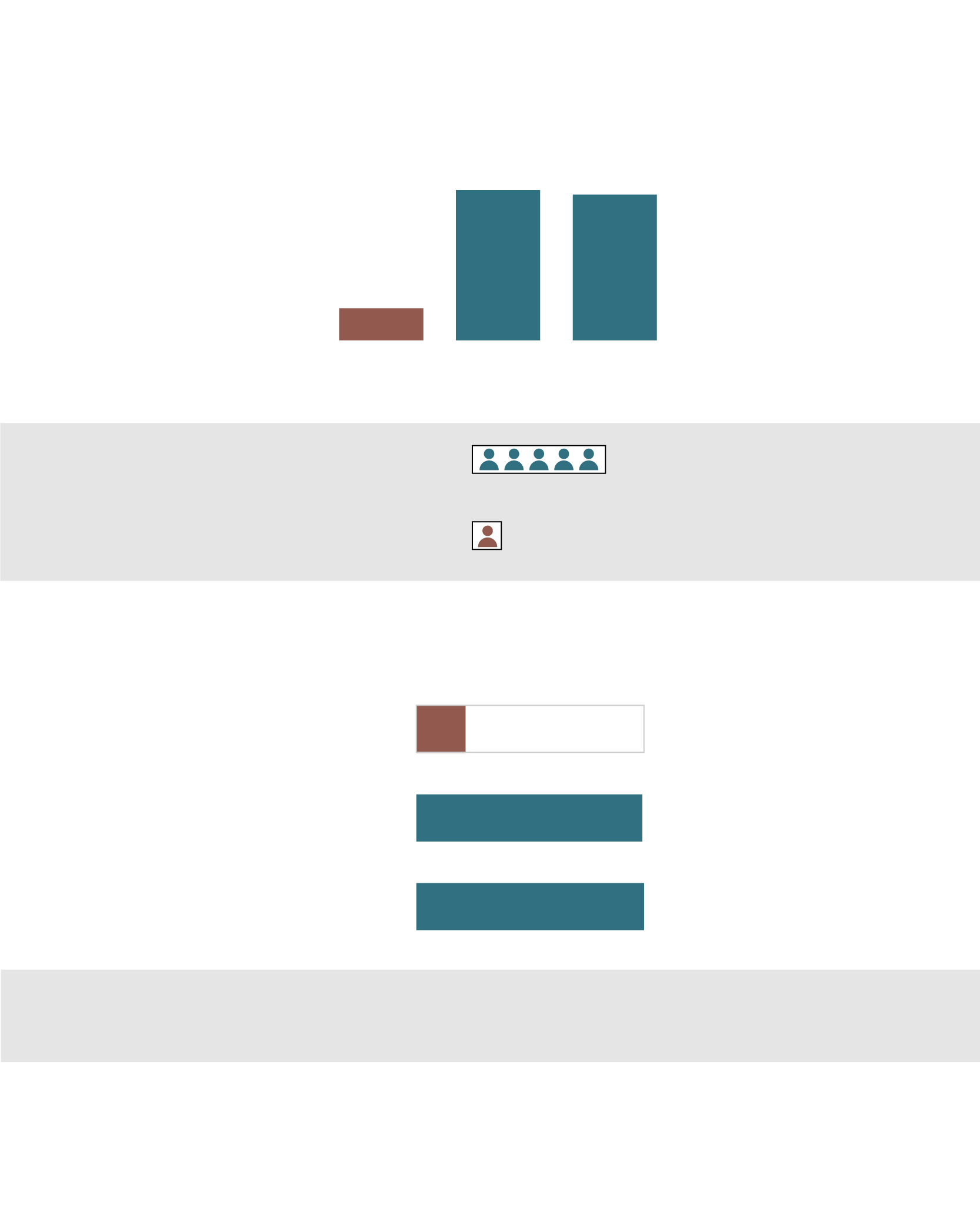

The inequality of Cuney Homes

The proportion of residents with bachelor’s or other graduate degrees is much lower in Cuney Homes than in Houston or Harris County.

32%

33%

7%

Houston

Harris

County

Cuney Homes

Area

For approximately every

residents

(25 years or older) with a college degree in Houston...

...there is

in Cuney Homes.

The annual per capita income among residents in Cuney Homes public housing complex is nearly one-fifth of that in Houston or Harris County.

Cuney Homes Area

$7,081

Houston

$32,521

Harris County

$32,765

The vast majority of families in Cuney Homes have annual incomes

below $50,0000. The median household income is around $11,600.

Source: Census Reporter. American Community Survey (2015-2019). Data for the Cuney Homes area corresponds to Block 1, Harris, TX. The margin of error for the population with the highest education in the area is +/- 6.7% and for the per capita income ± $ 1,297.

This emblematic mural, on the wall of Scott Food Mart, was painted after George Floyd’s death. It sits in front of one of the houses where he lived with his mother.